Kala is one of the largest and oldest parts of medieval Tbilisi, located on the slope of the right bank of the Mtkvari River. The toponym "Kala" referred to different territories at different times. For instance, initially, "Kala" referred to the citadel located on the ridge, but in the late feudal era, Kala became the name of a city district located below the citadel on the slope. The citadel itself is referred to as Narikala. Historical records document the relocation of the royal residence from Mtskheta to Tbilisi in the 5th century, consequently increasing the significance of Kala.

In the latter half of the fifth century, Tbilisi saw major development under King Vakhtang Gorgasali and his successor, Dachi. This era marked a transition in Georgian society as the feudal class came to power. By 523 CE, the end of royal rule in Kartli led to Tbilisi becoming the new capital, rapidly evolving into Georgia’s central hub for politics, culture, and commerce.

As Tbilisi rose to prominence as the capital, the city underwent significant growth and transformation. It endured multiple destructions throughout the centuries due to invasions, only to be rebuilt each time. The role of Kala also evolved over time: initially serving as the royal residence in the early Middle Ages, it later shifted to Isani (Avlavari nowadays) during the developed Middle Ages. However, under the reign of King Rostom (1565-1658), Kala once again became a royal district.

As V. Tsintsadze notes: "In the developed and late Middle Ages, it became a typical feudal city," and this character persisted until the 19th century.

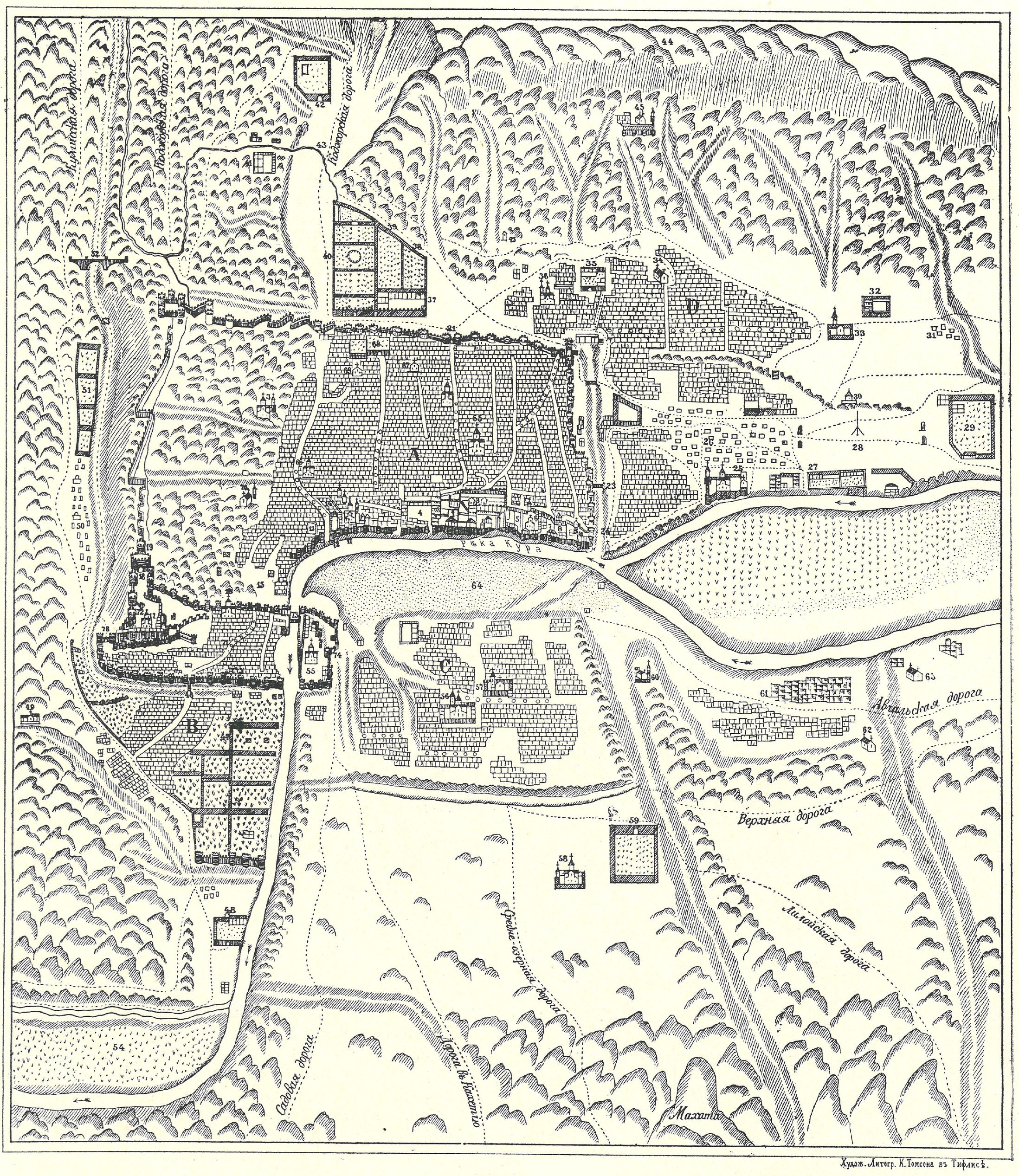

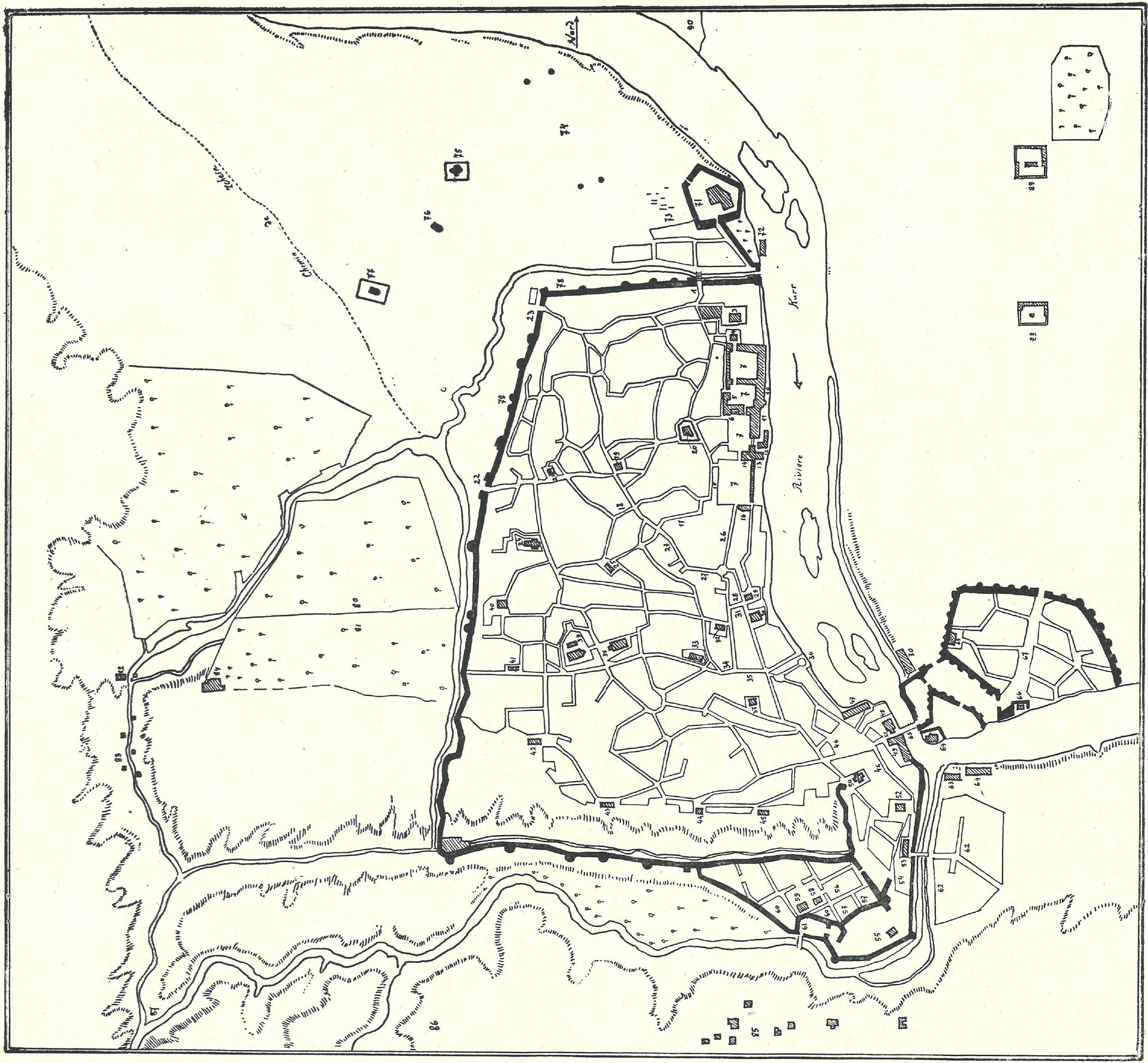

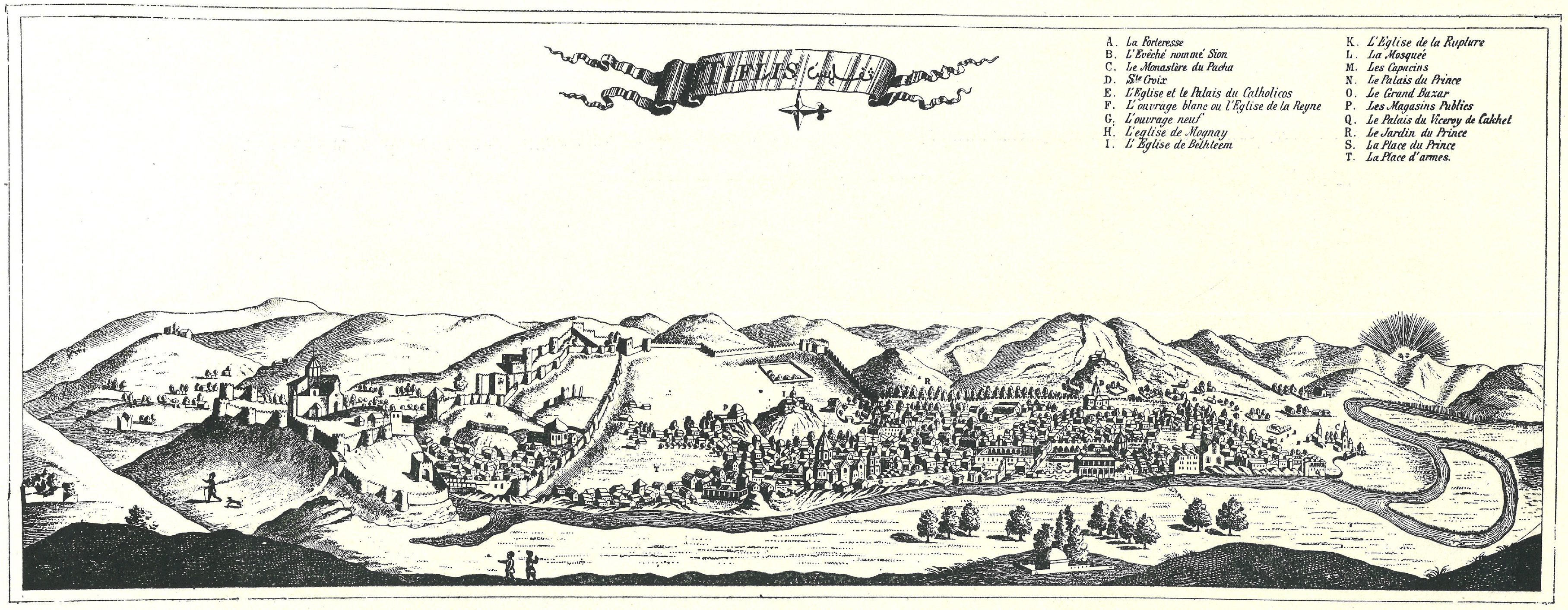

The map of Tbilisi, drawn up by the geographer and historian Vakhushti Bagrationi in 1735, and its description gives us an idea of Tbilisi at the beginning of the 18th century. According to this, Tbilisi was divided into four main parts, one of which was the walled district of Kala. In the 18th century (based on the 1782 map), this district was surrounded by walls, bordered by the Mtkvari River from the east, the current Baratashvili Street from the north, the current Pushkin Street, Freedom Square, and Sh. Dadiani Street to the Salalakis Ridge from the west, and the Salalakis Ridge itself to Abano Street from the south.

It is known that medieval Tbilisi had six gates. One was in Isani-Avlabari, and the remaining five should have been in Kala and within Tbilisi itself—the "Lower Gate" or "Water Gate" at the entrance of today's Shavteli Street, the "Middle Gate" or "Digomi Gate" at the intersection of today's Diuma and Vertskhli Streets, the "Upper Gate" or "Kojori Gate" at the intersection of Kote Abkhazi Street and Freedom Square, and others.

Kala was divided into two parts: "Lower Kala" and "Upper Kala," with these names assigned to these two districts according to the flow of the Mtkvari River. Upper and Lower Kala each had several micro-districts. Lower Kala included the Cliff District, located on the southwestern slope of the Salalakis Ridge, with the Citadel District adjoining it to the south. Below this, at the confluence of the Tskhavi River and the Mtkvari, was the Abanotubani District, which bordered the Seidabad District.

In Kala, both the Upper District and Lower Kala had their own distinct centers, which were in the form of squares. The center of the Upper District was referred to as the "Batonis Square" or "Upper Square," whereas the center of Lower Kala was known as the Tatar Square or "Lower Square." These squares housed markets, which were named "Upper" and "Lower" markets, respectively. The boundary dividing Lower and Upper Kala was marked by the so-called "Middle Market," situated on what is now Kote Abkhazi Street. During the late Middle Ages, Kala boasted two main squares: the King's Square, also recognized as the Upper Square or Military Square, and the Citadel Square, alternatively known as the Lower Square or Meidan. The King's Square served as a parade ground and a venue for noble gatherings, while the Lower Square was primarily focused on commercial activities. Additionally, there was an additional square named Kabakhi, situated outside Kala in Gareubani, which hosted jousting contests and public festivities.

In addition to the squares and markets, Kala housed various important buildings: palaces, caravanserais, and churches. In the Upper District were Sioni, Anchiskhati, and the other Churches. The Great Citadel Church, Norasheni, Mognisi, Cosma and Damian church, Jigrasheni, and Jvarismama Churches were in the Lower District.

After King Rostom moved the royal residence to Kala in the second half of the 17th century, the significance of this district increased even further. Upper Kala became the residence of the royal and noble classes, with its center being the King's or Batonis Square which coincides with today's Erekle II Square. The French traveler Jean Chardin describes King Rostom's palace with admiration, noting its large halls, the gardens and square in front of the palace, and the shops located on the square. The relocation of the royal residence here led to the mass settlement of Georgian aristocracy in this district. The Mukhranbatoni family built a house here, as did the Amilakhvari and Luarsab Batoni families. The Orbeliani family, the Eristavi family of Aragvi and Ksani, and other high-ranking clergy also acquired houses around Batonis Square. This district was mainly inhabited by Georgians.

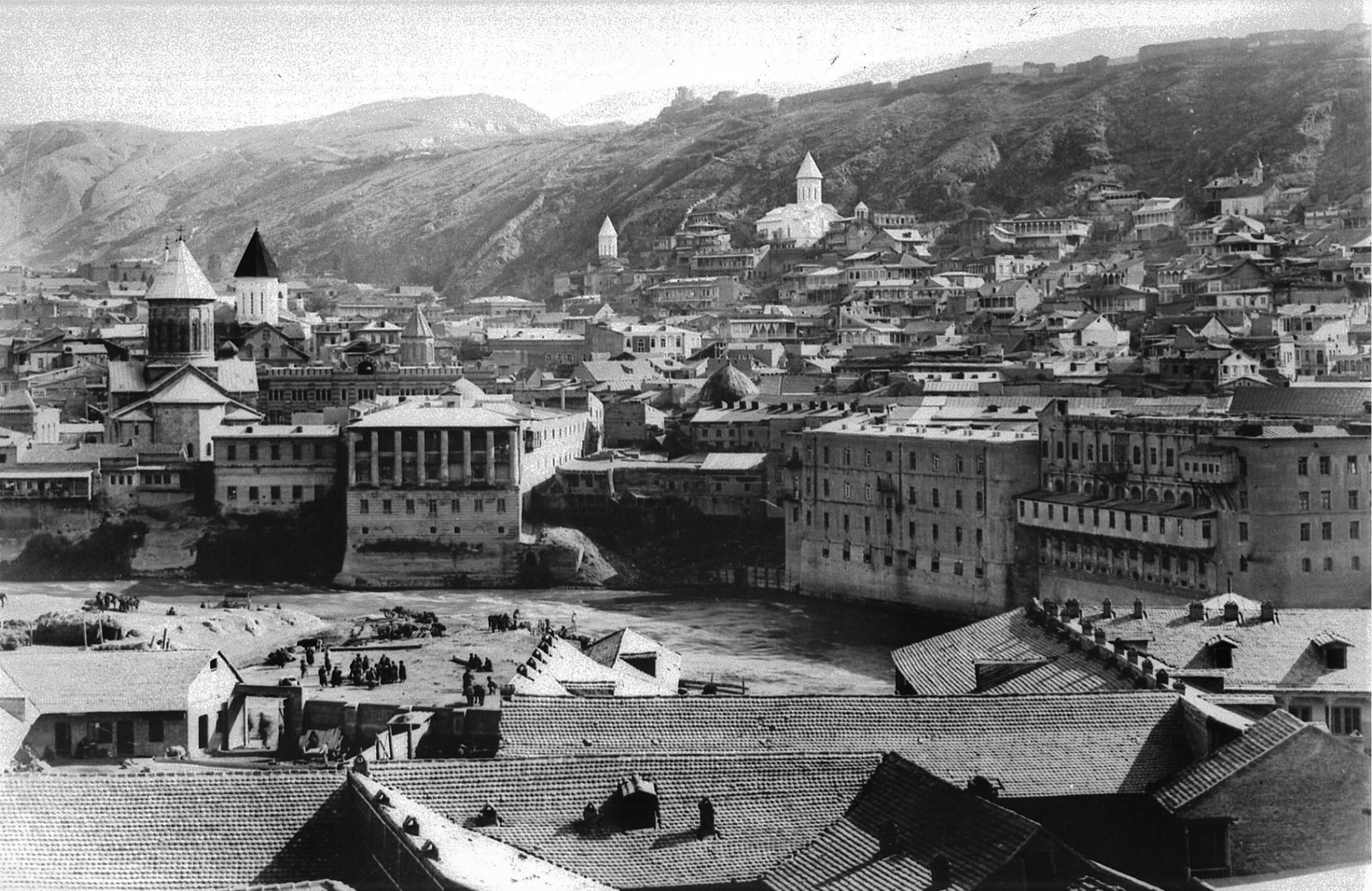

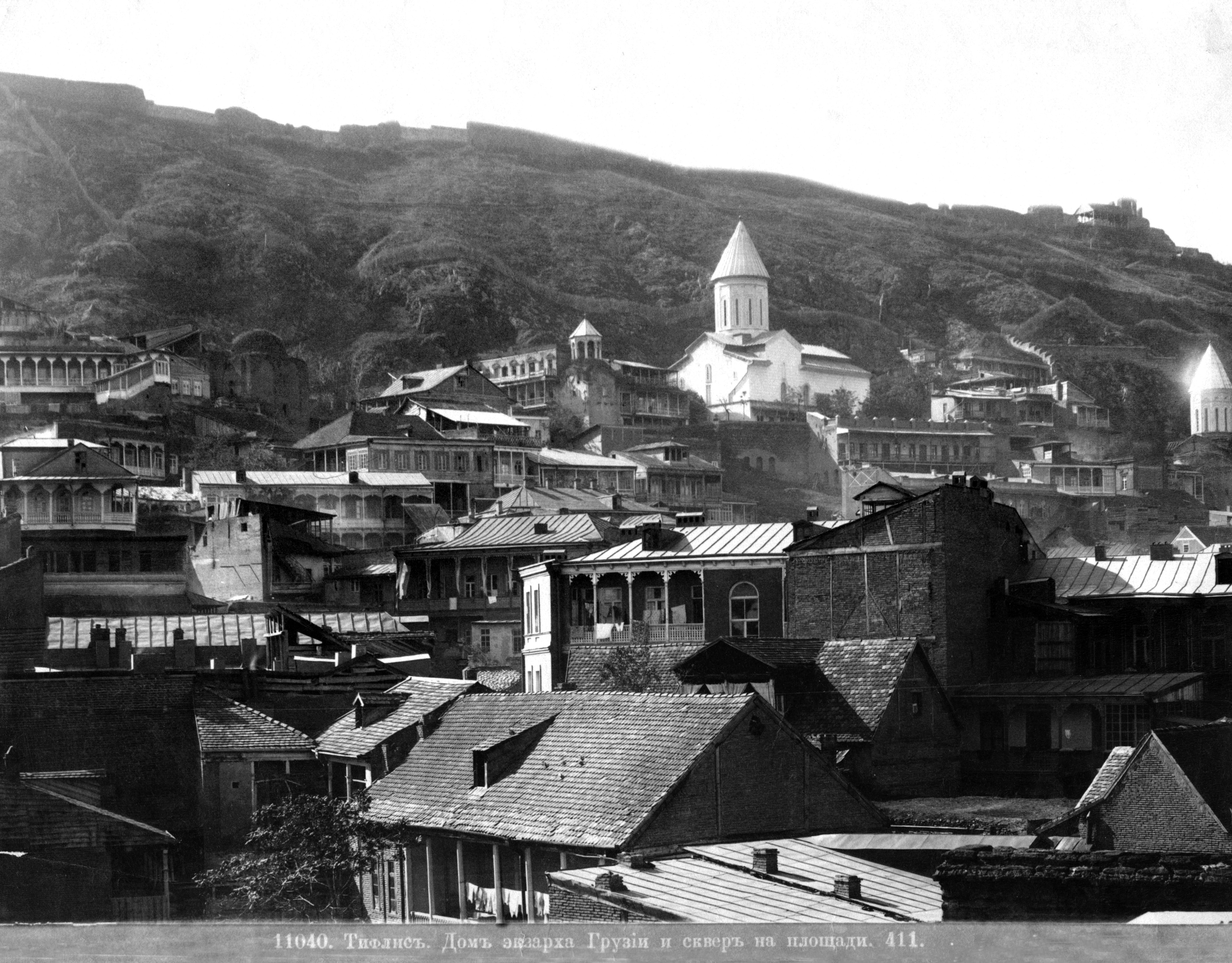

The center of Lower Kala, however, was Meidan, today's Gorgasali Square, where the middle and lower classes lived. This area was populated mainly by non-Georgians, including Muslims, Armenians, Jews, and Catholic missionaries. Lower Kala was densely built up, and unlike Upper Kala, it was predominantly characterized by houses with tiled and flat roofs made of old bricks, split stone, and river stone. This difference in development is clearly visible in the engravings published by travelers Chardin and Tournefort.

It should be noted that construction in Kala took place spontaneously and naturally over the centuries. In 1795, due to the Persian invasion, the medieval city of Tbilisi was destroyed. In 1801, Georgia was incorporated by the Russian Empire. The current appearance of Kala, which has survived to this day, was formed during this era, in the 19th century, although many changes also occurred in this district during the 20th century.

In the 19th century, when Tbilisi started to grow as a European-style city, changes in the city's layout began to affect the Kala district as well. V. Tsintsadze notes: “From the 19th century, Tbilisi gradually adopted the character of a bourgeois-capitalist city. The loss of medieval economic structures and the emergence of bourgeois-capitalist relations, the abandonment of old traditions and the adoption of new ones, as well as the disappearance of some architectural forms and the creation of others, were all influenced by internal and external factors operating over many centuries.” The city's planners and architects sought to integrate the medieval parts of Tbilisi with the new, modern urban developments. However, despite these efforts, the old part of the city, including Kala, retained much of its medieval character.

The district of Kala remained one of the leading centers of trade and craft in Tbilisi. This was particularly evident in the 19th century when the lower part of Kala, especially the area around Meidan (Gorgasali Square), was a vibrant commercial hub. There were markets, shops, caravanserais, and craft workshops. This part of the city was bustling with merchants, craftsmen, and traders from different parts of the Caucasus and beyond. The residential buildings in Kala were also distinctive. The houses were built in close proximity to each other, forming narrow streets and alleys, with many homes having balconies facing the streets or courtyards. These balconies, often wooden and intricately carved, became a characteristic feature of Tbilisi's architecture.

By the late 19th century and early 20th century, Kala began to experience more significant changes due to the influence of Russian urban planning. New streets were laid out, and some old buildings were replaced with new ones. Despite these developments, the core of Kala retained its historical character, with its narrow streets, old churches, and traditional houses.

In the Soviet period, Tbilisi's transformation continued, with new buildings, roads, and public spaces introduced across the city, including in Kala. However, the district's medieval core remained largely intact. The Soviet authorities did, however, undertake some restoration and conservation efforts.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was a renewed focus on preserving and restoring the historical districts of Tbilisi, including Kala. The post-Soviet era brought both challenges and opportunities for the preservation of the city's cultural heritage. On the one hand, there was a lack of funds and resources for comprehensive restoration projects. On the other hand, there was a growing awareness of the importance of protecting Tbilisi's historical and architectural legacy.

Several significant restoration and conservation projects have been carried out in Kala in recent decades. These projects have aimed to restore the old buildings, churches, and streets while also ensuring that the district remains a vibrant and livable part of the city. The restoration efforts have focused on preserving the unique architectural features of Kala, such as the traditional wooden balconies, old brickwork, and narrow alleys.

Today, the district of Kala is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Tbilisi with a rich history, unique architecture, and atmosphere. The district is also home to several important cultural institutions, including museums, galleries, and theaters. In addition, Kala continues to be a vibrant residential area where old and new coexist and where the past and present are intertwined in a unique way.

Author: Nina Bugadze, architectural researcher (PhD in Architectural Restoration), Ubani public program manager